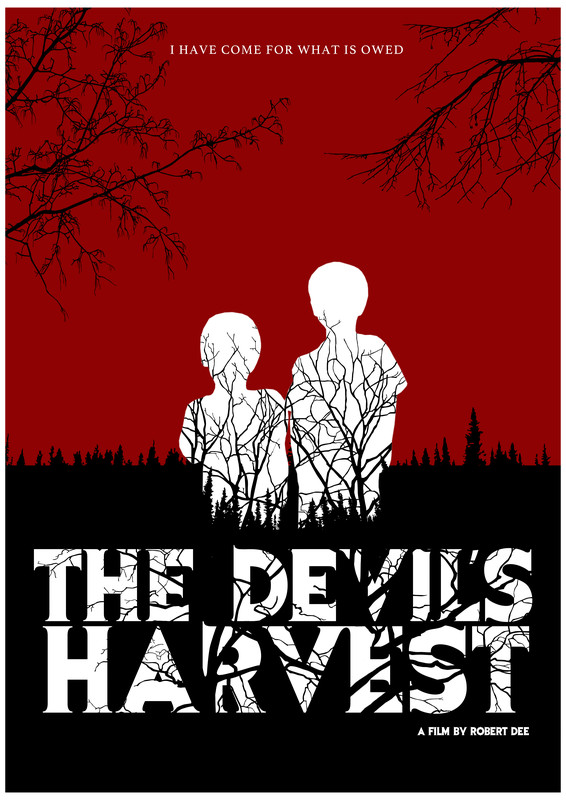

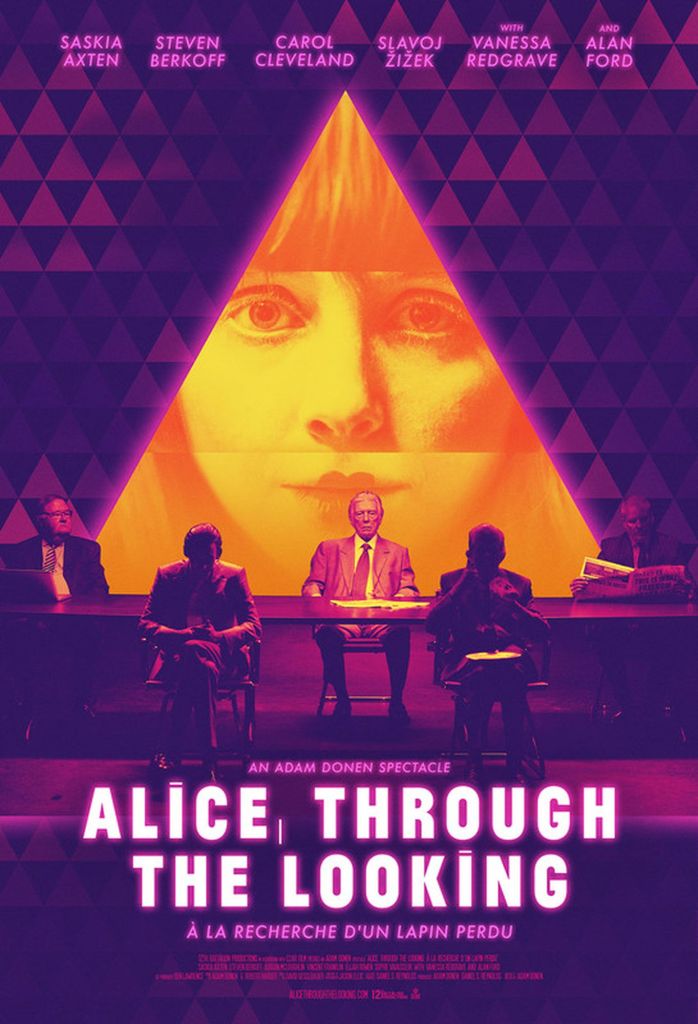

Rocks International Film Festivals wholeheartedly embrace the weird, wonderful and thought-provoking. Our feature film for LRIFF22 is no exception, ‘Alice, Through the Looking: À la recherche d’un lapin perdu’ by Adam Donen is a piece of work whose intricacies, quirks and hidden jabs reflect in no small measure the beguiling man behind the madness.

‘Alice’ is Donen’s first feature film, though he is an established and celebrated artist whose works range through the theatre, music and the world’s first fully holographic drama. The narrative – the term is used loosely – follows a young philosophy student as she searches for a man called “Rabbit” with whom she has spent a glorious night. As you can imagine, nothing goes smoothly and we are thrown into a chaotic but delectable journey down the rabbit hole into Donen’s dystopian London. ‘Alice’ is a special treat, for those enamoured by the works of Jean-Luc Godard, David Lynch and Monty Python, delightfully assaulting your nerves and bourgeois good taste at every corner. Donen is not shy about what he has to say and why should he be? We sat down with the creator and discussed ‘Alice’ in great detail but left many a stone unturned for those of you who will be attending the post-screening Q&A on 4 November at Whirled Cinema, London.

“I see it as a work that is designed to create problems in one’s response rather than to elicit a particular response“

What brought you to add film making to your very diverse and already budding portfolio?

The whole of ‘Alice’ has grown out of a character from an earlier theater script of mine ‘Declaration of Independence’. There was a character who wore a balaclava throughout and and then took off the balaclava and then her face and then the skin and finally the bones in order to try to find something underneath all of it. I also had the idea for a key which didn’t work in a lock and various other things along the way that would only really work with incredibly fast juxtaposition, incredibly bright colours, frantic cutting, and generally things that one couldn’t do on a stage but on film – and I do take the view that most things can be done on a stage.

Film is a discipline that I adore and for which I have the greatest respect, but for precisely that reason, the last thing I would ever want to do would be to have an idea and say, Well, I am a filmmaker, and therefore I should impose film on this idea because I think that denigrates both the idea and the media.

You are an artist who likes to impress with new forms and new ideas – do you think that is still possible in today’s saturated world?

In T.S Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent” he correctly points out that every new significant artistic achievement retrospectively rewrites everything that came before it, because if it doesn’t relate to it, it’s simply a fruitless branch that comes from nothing. This also means that if work from the past doesn’t have new things being built upon it, it is also a fruitless work that can’t serve anything, and that becomes useless by not having descendants. I suppose the short answer to your question is yes, it is possible and the reason it’s possible to invent new things is because we see the world in new ways.

If there’s any one thing that I have found myself wrestling over in my recent works is the problem of what it means to be an ‘I’ in the present where our actual experience is not the Dickensian linear. Rather our existence is one where this happens and that happens, or a person says something and talks and talks and talks and then somebody else talks and suddenly the entire world is changed by it so radically that any pretense to the story is absurd. I think one of the challenges of art in our present is how we depict and express what has happened.

Alice is a cacophonous joy – how did you go about putting all of your ideas, inspirations and thoughts into a script?

I didn’t plan a plot or anything along those lines, a series of scenes existed and needed to be put down on paper and through these I grew to understand what other scenes were also there and necessary. It’s really simply a case of trusting my instincts. I certainly don’t seek to impose myself on the work or ever to decide “it must do this”.

How did you then come to work with your varied and nostalgic cast?

First up was the issue of casting Alice and that was a tricky one. Over 1000 actors put themselves forward for the role and it was extremely difficult because I’m not used to that world. The business of self tapes is a difficult one for any actor as it’s virtually impossible to present yourself on video. We eventually cut it down to 40 or so and I was very lucky that one of them was simply unbelievably brilliant, instinctive and exactly what I had in mind. Saskia and I have completely opposite views on art and theatre but we have developed a wonderful friendship and she was the perfect Alice.

I struggle as for the most part I don’t like young British actors. It’s not their fault but the fault of the tradition in which they’ve been brought up. I adore and revere a generation of elderly radicals. People like Alan Ford, the whole Monty Python crew, Vanessa Redgrave and I think that it was very nice for them to have a work that was as radical as the stuff that they were doing when they were growing up. As opposed to fairly saccharin, heartfelt, but fairly normal stuff that is basically what we can do at the moment. It was fun to basically go all out on a limb with a bunch of my heroes.

Who wouldn’t be impressed by your cast – how do you work with your talent to get the most out of them?

It depends who it is, I don’t think I’m speaking out of school, in saying that Vanessa Redgrave was never going to do a self tape! My process for this film was very different with Alice and everybody else in the film. Alice is not only in virtually every scene, but whether we are looking through Alice’s eyes or how we approach Alice versus the view of the film is something that is heavily in the film. What I really tried to do with Saskia was to rehearse extensively with her before to the point where the character basically became hers. I’m very against giving backstories and anything like that. I’m very relaxed for actors to have an active role in the process and be inventing those for themselves. That’s a way in which they bring something that I could never bring just right just writing it and directing and all of those things. We worked hard to make Alice a character that we both instinctively knew no matter what happened when the camera was rolling.

The creative process with the others was really a stylistic process far closer to what Robert Wilson would do on stage with his choreographic processes. I feel older British actors and indeed some younger German actors, that physical control is something that one can work with so much and something that I really liked.

Long before I started making films I was given a book of interviews of great directors and Lars Von Triers made the argument that anybody who is a half decent craftsman in film should be able to do anything. The triumph is in creating in your own terms of work and that’s done by what it excludes, rather than by what it includes and that has stuck with me. Many people would probably take the view that I fail at it time and time again because of my wild divergences and form but indeed, precisely those divergences and forms is what I demand of my works.

Alice could be seen to be dealing with some rather controversial material which some people might not appreciate – was this your intention?

I don’t wake up every morning and think, right, who am I going to annoy today? At the same time, I do think that art is like politics and is something that is meant to divide rather than unify. If one is not picking the side that one’s on, or creating something that one knows, or is so far down a particular route that a lot of people aren’t going to like it, then I do rather question whether one should be doing what one’s doing.

How have you found the reception so far to the film?

Delightfully divisive, exactly as I might have hoped. I think that the last person who should ever comment on the meaning of a film is a filmmaker. I think they’ve got no right and it’s a mistake I made with previous work once, and I shall never do it again. Some have said it takes itself too seriously but I don’t regard it as a serious work, it just deals with terribly serious things. There are people who have either loved it or found it funny or found it excruciating all of which is great. I see it as a work that is designed to create problems in one’s response rather than to elicit a particular response.

Brecht says if one wants to write a poem that will be of use then one’s job as a poet is to keep it incomplete because the completion comes with what people do with it afterwards which is a sense I broadly have. I also think that because I’m not working with traditional narrative or three act plots and the very form of juxtaposition in which I’m working, means almost inevitably, there are going to be bits that people don’t like – and that’s fine. It’s also interesting, because I’ve discovered that the way that I consume many works is very different to the way other people do. On a Thursday evening I’m very happy to watch seven minutes from seven different films because I really want to explore an idea. I saw work at the Riga International Film Festival, which I shan’t name, but II think it was an exceptional film. The first 40 minutes of it was like nothing I’ve seen in a long time, really radical and then I thought the next 50 minutes were lyrical in a dull and banal way. And therefore I thought it was one of the best works I’ve seen in an incredibly long time.

How do you balance all of your work and projects?

Badly! I suppose, like most people, I’ve got more things in my life that I would like to do than I will ever do and that’s the nature of being human. In certain cases what’s needed is a lot of money, in other cases it’s a lot of time and in even more it’s the right people. I find myself in stupid periods for months on end, where I’m absolutely convinced that I’m going to do these three or four things and then somewhere along the way, irrelevant of money or time or even sometimes people, one of them just comes along and for whatever reason takes me over completely. And then that is the thing that must happen.

The Blues Brothers describe it as being on a mission from God and at a certain point one does just get the feeling in their soul that one is answering to a higher authority. At that point, one does whatever is necessary to complete the work. And then one feels, for a few brief moments, that one can absolutely and happily die at that point, and then one loses that feeling and then has to move on to something else.

‘Alice, Through the Looking: À la recherche d’un lapin perdu’ will be screening on Friday the 4th November from 8pm with an exclusive Q&A with the Director.