British cinema is littered with gems that failed to make their mark. Some now enjoy cult status, but many more have become lost treasures, scattered across the margins of film history . . . This is the first in a series revisiting such films, beginning with Jerzy Skolimowski’s excellent, if peculiar, 1978 film The Shout.

Based on Robert Graves’ short story of the same name, The Shout tells the story of Crossley (Alan Bates), a man who has ‘the terror shout’ – a fatal vocal technique learnt from an Aboriginal man while living in the outback for 18 years. Crossley enters the lives of Rachel and Anthony Fielding (Susannah York and John Hurt, respectively), exerting a strange control over Rachel with the magic use of her sandal buckle and pushing away Anthony in the process. This narrative is framed as a story told by Crossley to Robert Graves (Tim Curry) as he scores a cricket match at a psychiatric hospital.

This plot synopsis may sound a bit vague, but it is challenging to be concrete about such an enigma. It is precisely what makes this film so intriguing — and important. You are obliged to try to piece together the story while you are watching it, and frankly the film doesn’t make it easy for you. But, why should it . . ? It makes you as a viewer work, and this is one of the many joys afforded by this film.

Within its DNA are films like Performance and Don’t Look Now, which also require a bit of “piecing together.” It is, incidentally, a notable point that Nicolas Roeg was originally intended to direct this film. The Shout is not as mind-boggling as Performance (which, as an aside, even with three or four viewings I’ve never been totally convinced ties together completely). But its drastic cutting from one thing to another, great sound design and score which makes grandiose use of the organ and a synthesizer, combined with all-round stellar performances, place it – in this reviewer’s opinion – in the same league as Roeg’s films.

Certainly if Roeg had directed it, The Shout would be spoken about more. Polish-born Skolimowski is a fantastic filmmaker with a rich and eclectic filmography, but in my experience he is rarely discussed in critical circles. Another of his British films, Deep End (1970), is likewise a standout, and one that deserves far more attention than it receives. This was actually a US/German co-production shot in Munich, although set in Soho with a largely British cast. Discussing what constitutes a British film is, of course, outside the scope of this article, so we’ll move on . . .

Even if the director’s name fails to draw an audience, the cast of The Shout most certainly should: Alan Bates, John Hurt, Susannah York, Tim Curry, and even a young Jim Broadbent — all heavy-weights in the world of British film. It has to be said that the film’s success rests largely on the immese talents of the central trio of Bates, Hurt, and York, working in tandem under first-rate direction.

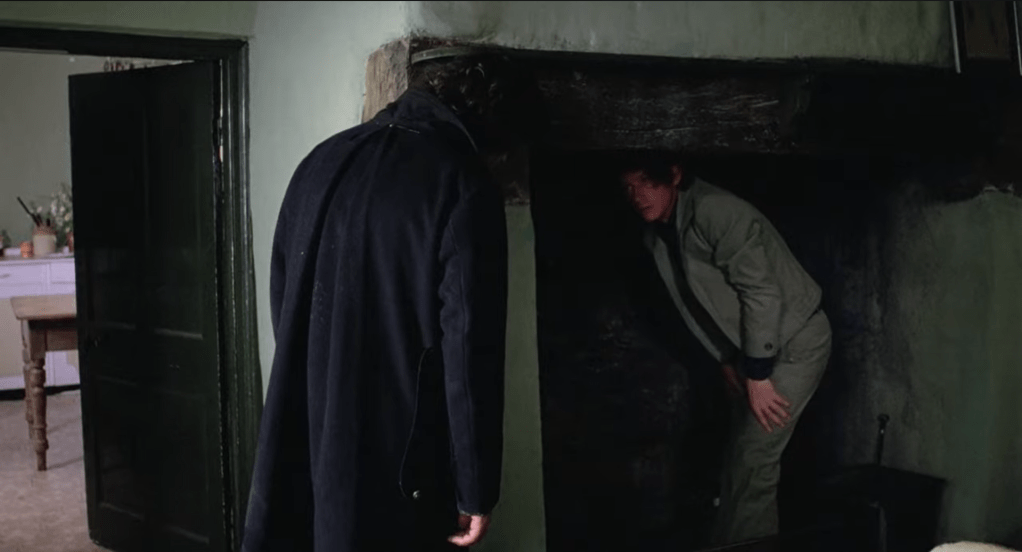

Bates was a large-framed, big chunk of a man. My first encounter of him was in Ken Russell’s Women in Love where he acts alongside another large, powerful, excessively virile actor, Oliver Reed. The famous naked wrestling scene demonstrated their powerful, big-block-of-man bodies. But I walked away from that film thinking it was Oliver Reed who towered above all, and that Bates was rather small. In The Shout, however, Bates constantly looms large in the frame in comparison to the thin and lighter-haired Hurt, and even more so next to York.

Bates’ physical presence does much to dominate the space – and this works alongside his cold and sharp delivery of every line and an almost never-slackening, penetrating gaze.

This is in stark contrast is Hurt, who cowers in the frame or under a fireplace. He is pushed over by his wife and struggles behind Crossley as they walk to the beach, getting a stitch in the process. He is, in every respect, a man displaced.

Unlike Crossley and Anthony, Rachel’s character is not as developed – to the film’s detriment. Her main role is to be fought over by Crossley and Anthony and to be under the influence of Crossley’s magic.

But York still delivers a strong performance, adding further ambiguity to the film. Does she know she is under Crossley’s influence? Her performance makes it unclear, keeping you guessing while adding further layers of mystery.

The matter is never quite resolved. On first viewing, I will admit to finding the ending unsatisfying, with the various stands seeming to just peter out in the midst of a large explosion. On revisiting the film, however, I understood how well-crafted it was and saw how everything comes together with an impressive coherence. There are still bits of ambiguity. But that’s fine. Films would be dull if we understood everything, and I don’t think there’s ever any point in trying to fathom every last detail.

In summary, The Shout is a film that deserves wider recognition. It should be considered alongside the likes of Performance, The Devils and Don’t Look Now – and all the other slightly odd, in-your-face British films of the 1970s – and recognised as a classic British film. Or a classic, full stop.

Article by Toby Bula-Edge