The talents of playwright, poet, theatre maker & filmmaker Mark C. Hewitt have been deservedly recognised at Rocks Festivals over the years as his work continues to challenge, surprise and captivate audiences and reviewers alike. A sequence of microfilm-poems with the overarching title ‘Les Coffrets’ played at Brighton Rocks 2022, and in June this year we were thrilled to screen his latest work ‘Songs of the Chambermaids’, which was joint winner of the Best Experimental Film Award.

‘Songs of the Chambermaids’ is a wholly absorbing, cacophonous and captivating original short film whose origins lie in an as-yet unperformed stage play called ‘Civilization and its Discontents’ from which Mark extracted part of the 9th movement to form the digital piece we see today. The play takes inspiration from Sigmund Freud’s eponymous book, examining the primary tension that exists between human beings’ desire for freedom and civilization’s demand for conformity.

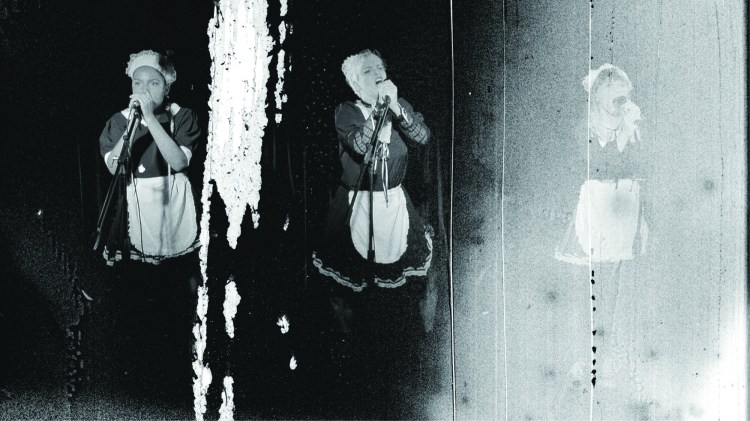

These notions are explored and reworked through the alluring and seductive chanting voices of three chambermaids, deftly performed by Marta Carvalho, Leann O’Kasi and Melissa Sirol, whose lyrics are seamlessly paired with the drumbeats and guitar music of Norwegian jazz percussionist Thomas Strønen. In three songs, the chambermaids discuss their philosophical ‘reasons for being’ and speak of the many trials and tribulations caused by living in a male-dominated, aggressive and violent world. “Men are not gentle creatures who want to be loved,” they chant with conviction. “They are savage beasts.”

To bring the project to life, Mark worked with long-time collaborator videographer and editor Matt Parsons. It is undeniable that ‘Songs of the Chambermaids’, which aims to critique the ethical implications inherent in the artist/subject relationship, adroitly marries with Matt’s work. Through an unquestionably sensible choice of black and white and dysphoric flickering film which oscillates between the increasingly imploring chorus of our chambermaids and a series of evocative and ultra-violent images, ‘Songs of the Chambermaids’ transcends the realms of a ‘normal’ viewing experience. At the film’s climax, a relentless torrent of subliminal images is unleashed evoking mankind’s history of war and atrocity.

“It’s the sort of piece which comes out through the fourth wall and addresses its audience directly, or at least appears to, which some people like and some people don’t”, comments Mark. ‘Song of the Chambermaids’ is certainly a film which I wanted to watch on repeat, alone in a dark room with the sound reverberating around me. At each viewing I found myself totally hypnotised by the words, the rhythmic chanting and the chambermaids themselves, leaving me with disparate feelings. It is a piece of work that demands a discussion. Perhaps it is the existential questions that strike such a chord, or its exploration of the misogynistic and arrogant male world we unfortunately continue to live in. Whatever the reason, ‘Song of the Chambermaids’ is an extraordinary work of experimental cinema and it was my utmost pleasure to be able to work with Mark at both reviewing this piece and elucidating some of the filmmaking practices behind ‘Songs of the Chambermaids’.

How did you come to be working with Thomas Strønen on this piece where, as mentioned, the music is woven so seamlessly into your written words.

In 2013 I received a grant from the Artists International Development Fund which sadly no longer exists, to initiate a collaboration with Norwegian musician and composer Thomas Strønen related to a play I was writing/developing called ‘Civilization and its Discontents’. I was aware of Strønen through his work as drummer and sampling percussionist with a band called FOOD, whose sound I felt connected with the world I was trying to create in the play. Something about the mixture of jazz instruments and otherworldly electronics. I emailed him out of the blue and it happened to coincide with a period when he wanted to do less gigging and more composing. It was probably while I was in Oslo for a first discussion of the project that he must have mentioned that he was also working with a drum ensemble at the Norwegian Academy of Music, where he’s an Associate Professor and I felt there could be a synergy between this drum music and the chorus I was imagining for my play.

It will probably sound a bit crazy but the idea for ‘Songs of the Chambermaids’ came to me in a vision. By a vision, I mean I was awake all night in a heightened imaginative state, doing nothing other than lying down visualising, thinking things through and making notes until the dawn broke.

Later, I made an application to the Norwegian Composers Fund, which is how I commissioned the music. Strønen sent me about an hour’s worth of music to use or not use as I wished. In that sense it was quite a loose and trusting collaboration. With some of this music I immediately knew what I would do with it as it had a particular role in separating sections of the play but the music for drum ensemble was less obvious. It will probably sound a bit crazy but the idea for ‘Songs of the Chambermaids’ came to me in a vision. By a vision, I mean I was awake all night in a heightened imaginative state, doing nothing other than lying down visualising, thinking things through and making notes until the dawn broke. To give a bit of background, the play I was working on is set in a louche private members establishment called The Paradise Club at a time of violent civil conflict. There is a chorus of chambermaids and night porters who are the last remaining staff at the establishment. I’d conceived the notion (sort of a conceit, really) that this chorus might recount the narrative arc of Sigmund Freud’s essay Civilization and its Discontents but in their own words and for their own reasons. However, my attempts to write this hadn’t been at all convincing; it was difficult to find the right tone or work out which source material to use and which to leave out. In the vision, the idea came to me that this narrative could be delivered over music for drum ensemble in the voices of the three chambermaids, who would transform themselves into a sort of girl band. It was an exciting and appealing idea.

Magical moments occurred when certain lines just landed beautifully and resonated with the music.

But it proved to be incredibly difficult to write because of the complex, ceaselessly shifting rhythmic patterns. It actually took me about a month or so to complete a first draft, working on it every day, listening over and over again to the tracks, extending the lyric bar by bar, the lines one by one, with various translations of Freud’s essay open on the desk in front of me, from which I might steal a phrase or somehow refashion or paraphrase in a way that responded to the highs and lows of the music and nuances of character. Each track and each part of each track required a different strategy, there was no formula – but then magical moments occurred when certain lines just landed beautifully and resonated with the music. The process also had an editorial value in that the musical structure determined which content from Freud’s essay could be used and which couldn’t. It was a crazy undertaking. No one in their right mind would do such a thing.

Of course, once the task was completed, I then realised how difficult it would be to perform. And it was because I knew that it would be difficult to perform that I started trying to develop the sequence separately, ahead of the rest of the play – firstly, just to prove that it could be done, then to try to get it better and make a record of it. And it’s that process which led to the digital/film version which now exists, and which, I think, can be considered a thing in its own right.

Your flashing images are hypnotic, terrifying and incredibly evocative, but also achieve a delicate balance and cohesion. How were these first approached and then brought about with Matt Parson?

I think we both felt that the performance itself, in filmic terms, wasn’t enough. It somehow needed more. More distress.

The flashing images were really down to videographer and editor Matt Parsons. We filmed ‘Songs of the Chambermaids’ following a 10-day residency in Portugal in 2021 where myself and the three actresses were developing the piece for a live performance. Pressures of time and money meant that when we got back to England we had to shoot the sequence in just a 4 hour session. Matt still hadn’t seen the performance so didn’t know what to expect – although he had read a draft of the play. Pretty much as soon as we’d finished the filming he was starting to talk about an idea for dropping in subliminal images – related to the themes of the play – an idea he associated with the director Buñuel. Unfortunately, Matt’s crappy old computer that he had at the time couldn’t handle the density of the footage and went into meltdown so it took him another year to get together the resources to get a better machine and we had actually only just finished the current edit when it was submitted for Brighton Rocks. I think we both felt that the performance itself, in filmic terms, wasn’t enough. It somehow needed more. More distress. I identified the key places where I thought Matt’s subliminal interventions would work then left him to it. We also bought in a lot of extra film damage so that we could disrupt the surface textures – sometimes quite violently – throughout the piece. Matt feels it helps the words make sense and I think he’s right.

I’m proud of the fact it’s artist-led work and made with zero infrastructure on minimal resources. It’s great to get to a place where something is so wrong it’s right.

You screened at Brighton Rocks in June. As it is such a challenging piece, how was the audience reception from your viewpoint?

The audience reception at Brighton Rocks: I think it was mixed actually. The piece is quite demanding – it asks a lot of an audience – and it came at the end of quite a long 2 and a half hour session so I think some people who’d been in the theatre for quite a while seeing various other pieces couldn’t take it – it was just too much – at that time – within that specific context. Those I did speak to picked up on different things. One woman talked about liking the differences between the three characters/performers and their different accents, (none being English). It’s the sort of piece which comes out through the fourth wall and addresses its audience directly, or at least appears to, which some people like and some people don’t. The last time it was performed live, some guy commented in an after show Q&A that he found it “pornographic and disturbing”. I don’t think it is pornographic but I was quite amused by the comment.